Papo & Yo

Publisher: Sony Computer Entertainment / Developer: Minority / Platform: PS3

“To my mother, brothers, and sister, with whom I survived the monster in my father.” –Vander Caballero

So begins Papo & Yo (roughly “Papa & Me”), immediately followed by a scene where a young boy hides in a closet from his abusive alcoholic father before escaping into a fantasy land. At this point I braced myself for a game that was either going to be an important statement or an uncomfortable mess.

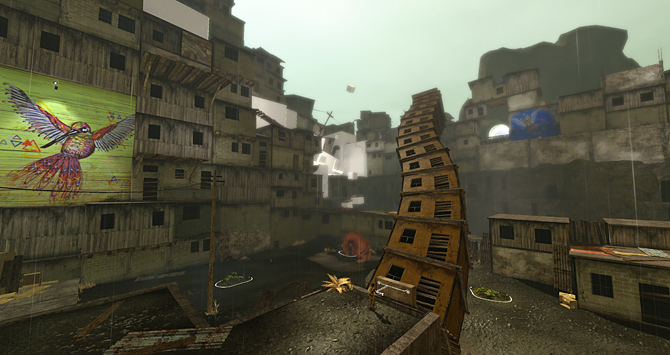

Papo & Yo is a puzzle platformer that takes place in the mind of a boy named Quinco. This fantasy land looks similar to the real world, but is a place where structures can be manipulated through the power of imagination. Wall drawings have magical properties, and moving around boxes can move nearby buildings that he imagines them to be. Quinco also has an action figure named Lula, who aids him. The imagery could have been a little more fantastic, but because of the way it always remains grounded in something resembling reality, you can easily picture this being an ordinary kid walking down the street while imagining this pretend adventure in his head.

The opening sequence makes you think the monster is a creature to be avoided, but most of the time he’s harmless. His two main interests are sleeping, and eating the fruit that falls from trees throughout the game. He even ends up being helpful in a passive manner, acting as a puzzle element that can be easily moved around by getting him to chase after tasty fruit. I even started to warm to Monster after he rescued me from a puzzle gone wrong. He was fine as long as I kept him from eating his favorite snack of exotic frogs, which would cause him to start hitting me.

In terms of story, similarities can be drawn to Alice: Madness Returns, with both games featuring a character dealing with trauma by escaping into a wonderland. Except Papo & Yo is more down to earth and real, and thus more sobering. Not to mention its story actually makes sense. This is the sort of videogame story American McGee wishes he could write.

In some ways the gameplay also reminds me a little of Ico, minus that game’s two most tedious elements – the escorting and the enemies – which isn’t to say it’s not without flaws of its own. The world is constructed in such a way that it seems meant to be explored, filled with tempting nooks and crannies, and yet everything is either dead ends with no purpose or ledges blocked by invisible walls. At one point control was even taken away from me so that I would stand still on a platform that was about to drop, rather than running past it, because the linearity of the game required it. And while there are collectibles to find, resulting in at least a little exploration, they don’t actually become collectable until the second playthrough.

There are also issues that result the game being difficult in ways it probably wasn’t meant to be. While there are always issues associated with precise platforming in 3D, my only real problem was how hard it sometimes was to judge and time double-jumps before gliding (one of Lula’s useful abilities). I lost count of how many times I’d miss a jump by such a small fraction that Quinco’s feet would merely nick the side of the platform, and I’d drop down and have to start the platform sequence over. Never have I been more aware of the absence of a simple ledge-grab ability.

There are other little annoyances that result in the game feeling dated or just cheap. During one platforming sequence, I kept clipping through a section of platform where it butted against a wall, and had to do it over several times. In the same area, activating a puzzle element would result in the camera repositioning itself in such a way as to make avoiding Angry Monster harder. And the way in which people’s mouths don’t move when they talk makes the game feel a decade older.

But these are all minor complaints. In all honesty, I think the biggest mistake in the game was starting it with that dedication, and the inclusion of that opening scene.

The third act unfolds so beautifully, in a way that would have been perfect for unveiling the twist, if the twist hadn’t already been given away by the dedication and opening scene. If that intro hadn’t been there, few people would have ever suspected what the game was actually about until the third act. It would be that thing critics wouldn’t dare reveal in reviews, insisting that people experience it for themselves. Everyone who played the game would be having discussions about the lift ride, or the moment they first saw that beer bottle, or the transformation of the statues at the end. People would even be playing it a second time just to see if there was other symbolism or context they missed the first time around. I really think such a mind-blowing twist could easily have generated the same level of word-of-mouth hype that Journey experienced just after launch.

But what’s interesting to note here is that my biggest complaint with the game isn’t about a gameplay-related decision made by the developer, but a storytelling decision, and what that means in relation to videogames as a potential storytelling medium. In making the mistake, this game has managed to highlight just how effective a videogame can be at telling a story, when done right. One day, when colleges offer courses on Storytelling In Videogames, Papo & Yo will be one of the games they teach..not because it’s a masterpiece, but because of the way it demonstrates how dramatically the placement of a single scene can impact an entire story.