Mario Origins: How A Popeye Game Became Donkey Kong

The year is 1990. Nintendo has just received the latest “Q Ratings” report — a long-running popularity poll that ranks celebrities and fictional characters by weighing their popularity against their familiarity — and the latest results show that Mario now has a higher “Q Score” than Mickey Mouse.1

This in itself was not unusual. Characters had overtaken Mickey before, only to eventually drop back down again. What was unusual is that this time, the character was from Japan. But how did a toy company in Kyoto end up with a Brooklyn plumber as its mascot?

Critical Kate is on the case.

This is a transcript of the video linked above. The text version contains only a fraction of the visuals; I recommend watching the video for the full experience.

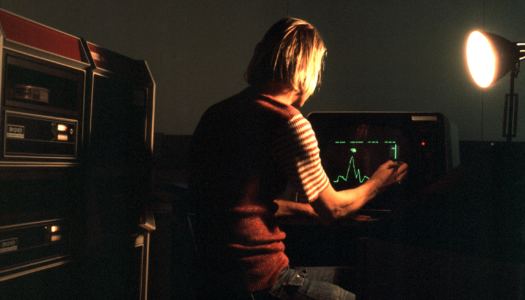

Nintendo headquarters. 1981. Game designer Gunpei Yokoi is overseeing the next wave in the Game & Watch series — a popular line of handheld games with LCD screens — when his boss, Hiroshi Yamauchi, comes to him with an assignment: Design a game that will bail out Nintendo Of America.2

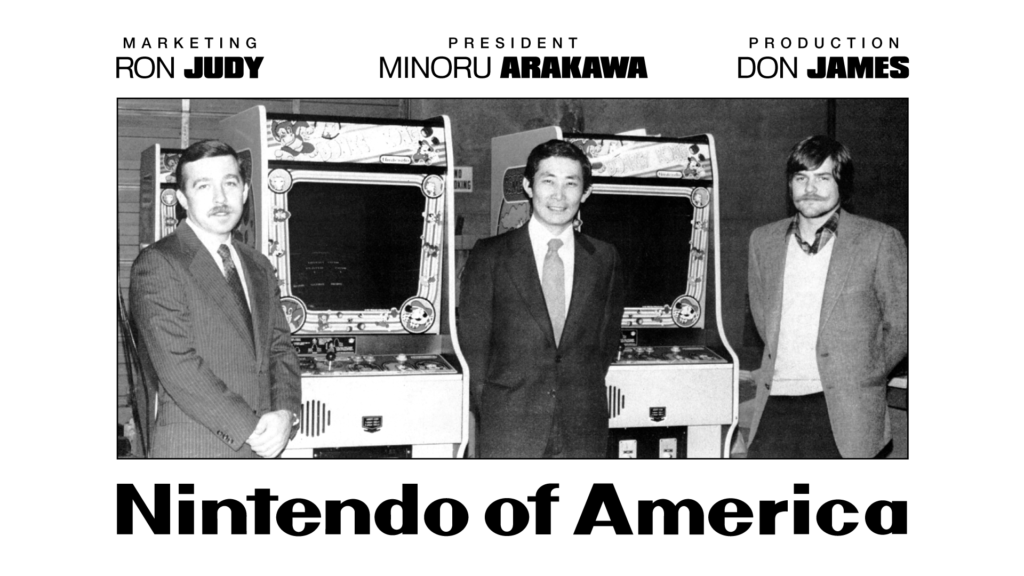

Nintendo had been making arcade games since the 1970s, but its American distribution had always been handled by American companies.3 Nintendo Of America was established in 1980 for the purpose of doing it themselves. Yamuachi appointed his son-in-law, Minoru Arakawa, to head up the company in New York City.

The first two games from Nintendo Of America were shown at the big coin-op trade show in October — the same trade show where Midway demonstrated an unassuming little game called Pac-Man.

In HeliFire you played as a submarine, from which you fired missiles at helicopters while dodging projectiles. It was nothing special in terms of gameplay, but visually it was a bit unusual, thanks to an obscure graphical trick that filled the background with smooth gradients instead of flat colors.

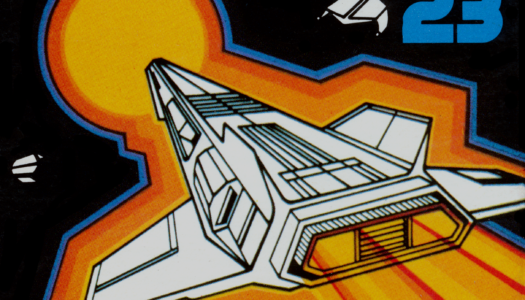

Radar Scope was even more visually impressive. On top of being the first game to include a “damage meter” or health bar, it was also the first game to depict a Space Invaders or Galaxian style shootout from a 3D perspective, with distant ships gradually growing larger as they approached.

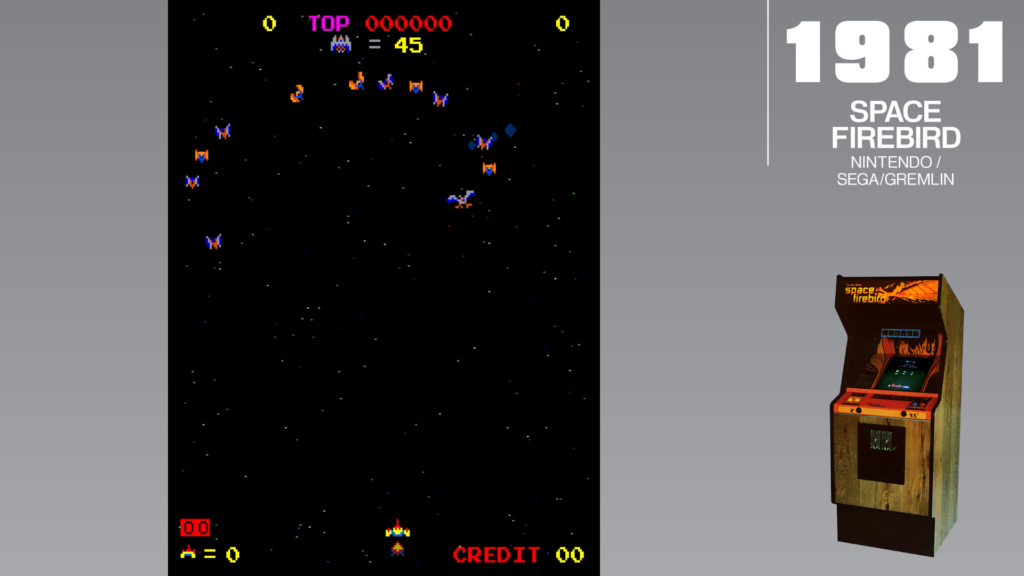

Compare this to Space Firebird, a third Nintendo game at the show, but one that was already being distributed by Sega/Gremlin. Although the gameplay had a bit more variety than Radar Scope, visually it looked no different from any other top-down shoot-em-up released that year.

In Japan, Space Firebird was a moderate success, making it as high as the #3 spot in Game Machine magazine’s weekly operator polls. Radar Scope, on the other hand, was able to reach the #2 spot, making it ever so slightly the more successful of the two.

But in America it was a different story. Here Space Firebird was only a minor success, getting only as far as #14 in Replay magazine’s monthly operator polls, while Radar Scope — possibly due to Nintendo Of America not yet being as well-connected as Sega/Gremlin — didn’t chart at all.

Of the 3,000 units Arakawa shipped from Japan, less than a third sold through during the game’s crucial first months. Facing such a devastating blow, Arakawa got on the phone to his father-in-law with a request, who in turn went to Gunpei Yokoi with an assignment:

Design a game that will bail out Nintendo Of America.

But, there’s a catch. The game has to run on the same hardware as Radar Scope, so that Nintendo Of America can convert their warehouse full of old games into this new one. The only problem is, Yokoi is kind of already busy. But luckily, he recently began mentoring the company’s graphic artist into becoming a game designer, and decides to put him on the task. His name is Shigeru Miyamoto.4

Replacing Radar Scope

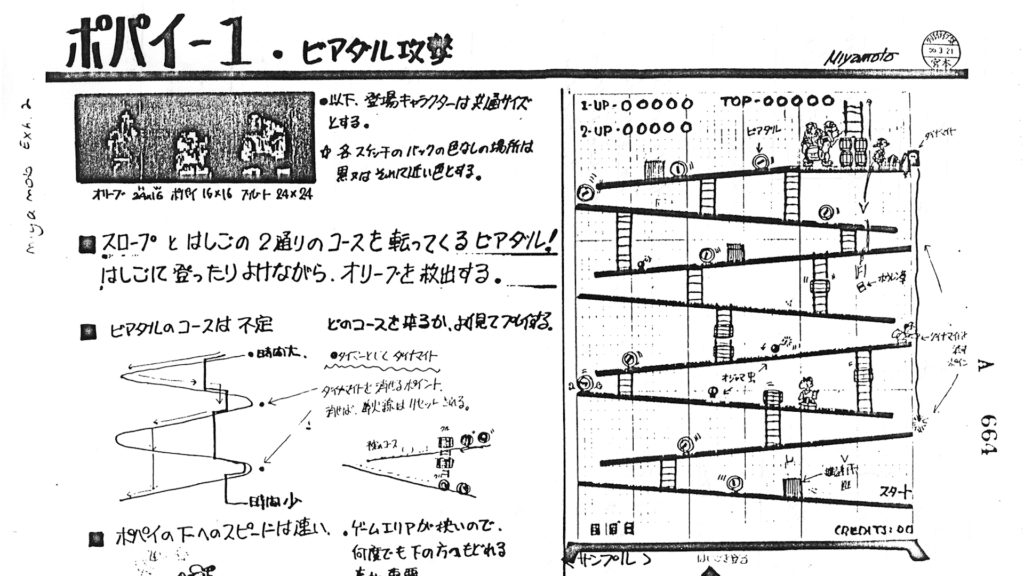

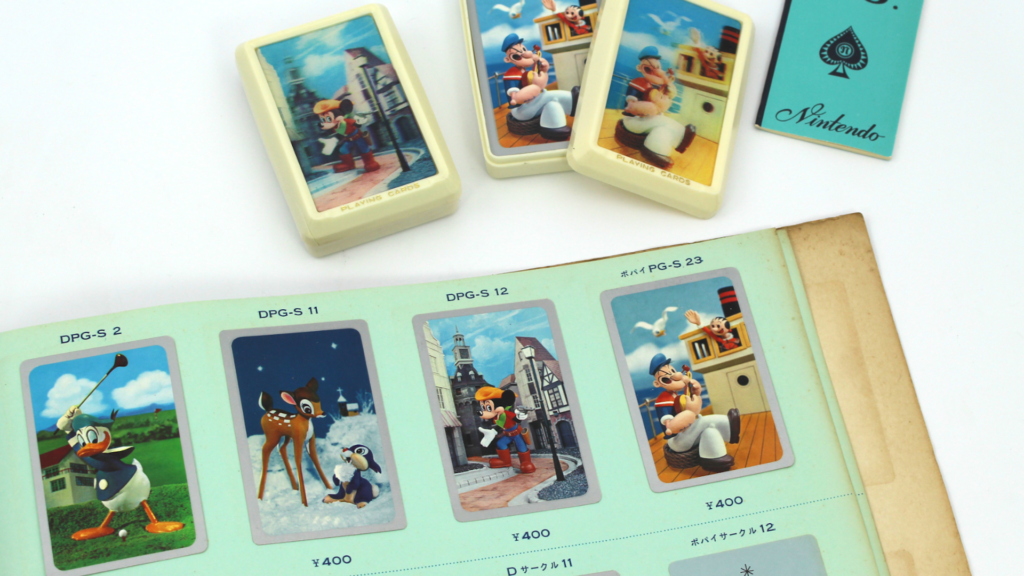

Miyamoto is working on Game & Watch designs, the next wave of which is going to include iconic characters like Mickey Mouse and Popeye, properties Nintendo has been licensing on toys and playing cards since the 1960s. Miyamoto was initially working on the Popeye Game & Watch, so when the Radar Scope project comes down the line, they figure, why not make a Popeye video game?

Yokoi thinks the setting should be a construction site, inspired by the iconic “sleepwalking Olive” sequence that was recycled numerous times by Popeye’s own animators. Yokoi’s favorite bit is near the end of the short, when it looks like Olive is about to walk off a girder, only for new ones to keep swinging into place, a concept it appears he’s already explored in the game Manhole.

Miyamoto plays around with an idea where the girders become elevators5 — a concept later explored in Mario’s Cement Factory — but for now they settle on a concept involving rolling barrels.

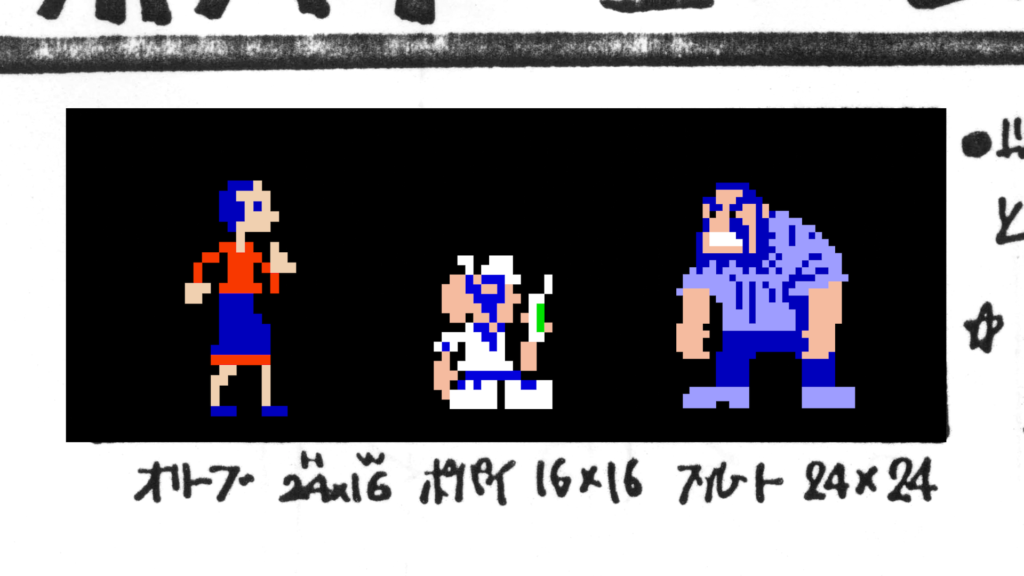

This early sketch was discovered by gaming historian Norm Caruso while going through old court files. The moment I saw it, I wanted to see if I could translate these blurry Xerox’ed graphing paper drawings into finalized pixel art.

But almost immediately, I discovered a problem. The Brutus design only worked if I increased the number of pixels, which would make him a giant in comparison to the other characters. Miyamoto must have realized this as well, because by the end of March he replaced Brutus with a giant ape. Donkey Kong was originally going to fight Popeye.

The inspiration for Donkey Kong was clearly the movie King Kong, but was the inspiration direct or indirect? Popeye fought a giant ape just nine months after the original movie. But another possibility is that Miyamoto had simply been playing a lot of Crazy Climber, Japan’s third most popular arcade game of 1980.

Contracting Ikegami Tsushinki

In 1997, Miyamoto’s ape sketch was published in a Japanese tech journal called Bit magazine, for a feature on the making of Donkey Kong written by one of its programmers. Hirohisa Komanome is an employee of Ikegami Tsushinki, a TV broadcast equipment manufacturer that had programmed all of Nintendo’s video arcade games up to this point.

The sketch is dated March 31st. On April 6th, Ikegami assembles a project team of four software engineers — including Komanome — with a tight projected turnaround of just two and a half months. Their first task is to evaluate Miyamoto’s pitch, and to brainstorm possible improvements.

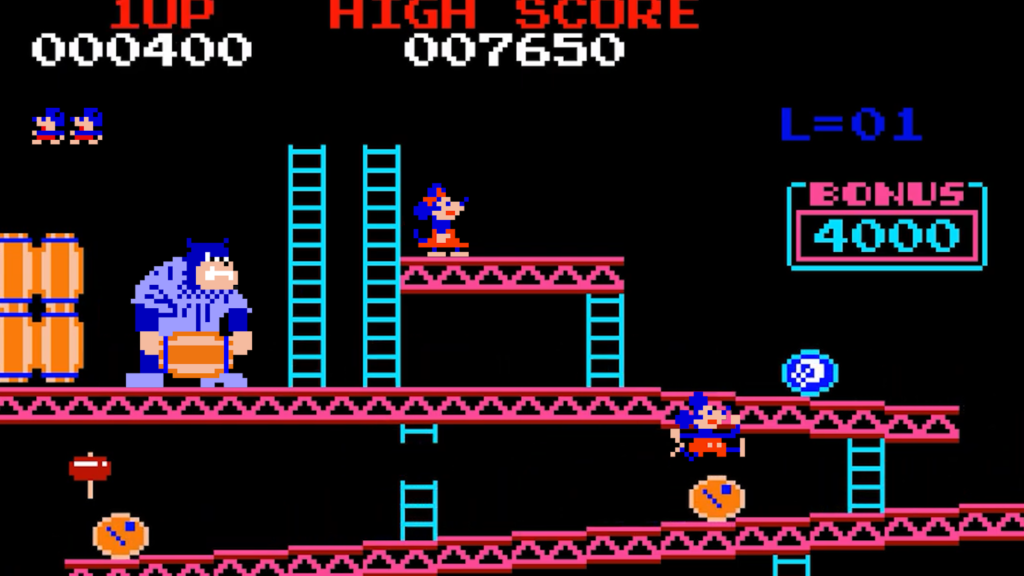

The biggest change to come out of this first week of brainstorming is the concept of a jump button.6 The initial game pitch is little more than a ladder climbing game in the vein of Space Panic, but Miyamoto’s take doesn’t even involve digging holes. Instead, you mainly avoid danger by climbing ladders, which the programming team feels is a little too passive. Someone points out that if barrels were being rolled at Popeye, he’d likely just jump over them.

The team would also like to see more variety, since at this point the game is merely a single repeating stage, with only an occasional special stage to break things up. Not that this is unusual. In 1981, most games are still just a single stage, because the primary goal of an arcade game is to achieve a high score, rather than to reach any sort of ending.

But the programming team has been playing a popular new game called Scramble.7

This extremely influential side-scrolling shooter was revolutionary at the time for featuring five distinct stages that each required a different strategy. This encouraged players to try to get just a little bit further every time they played, in order to find out: “What happens next?” This primary objective is spelled out on an opening screen that asks: “How far can you invade our scramble system?,” a message Donkey Kong will mimic by asking, “How high can you get?”

But if the game’s going to have multiple stages and a jump button, the programming team feels that the theme of one of these stages should be jumping. This gives Miyamoto a reason to bring back the vertical elevators, which he previously felt might have been too difficult for a player to walk onto, but now the player can jump. The resulting level design will instantly invent the entire platform genre.

But soon, a new problem arises: Popeye has to be replaced.

The reason — according to both Komanome and Yokoi — was a combination of the difficulty in making a 16-by-16 pixel sprite look like Popeye, but also unspecified licensing issues.

Instead, Nintendo will roll Popeye into a less time-sensitive project, one that won’t be shackled to ill-fitting hardware. This new Popeye game will utilize a technique previously seen in Nintendo’s Sky Skipper that allows them to draw large character art at twice the normal resolution — at the expense of the background art which needs to be greatly simplified.

Making Mario

In the meantime, however, Miyamoto needs to figure out who in the world is going to be fighting this giant ape. And the clock is ticking.

Since the game is set on a construction site, Miyamoto concludes that the most obvious solution is to make the player character a blue collar worker. As an added bonus, dressing him in work overalls helps to define the shape of his arms when he runs, while giving him a mustache helps to define the shape of his nose.

Miyamoto is so pleased with the results, that he immediately begins picturing the character appearing in a wide variety of scenarios — the same way that comic artists like Osamu Tezuka would frequently re-cast their characters in different stories as if they were actors.

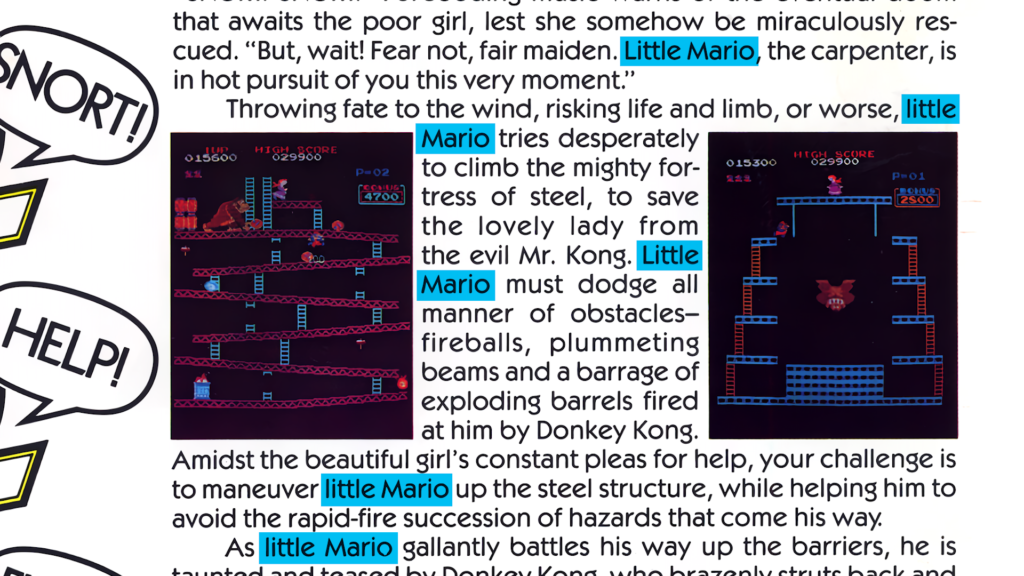

Miyamoto wants to name the character “Mr. Video,” but when the cabinet ships to Nintendo Of America — which has since relocated from New York to Seattle — the English version of the instruction card dubs him: “Jumpman,” likely in reaction to the recent success of Pac-Man. However, Arakawa & Co. quickly take to calling him “Little Mario,” in reference to their new Seattle landlord, Mario Segale. Within months they insert the name into the description text of the American arcade flyer.

And that’s how Mario became Mario. But even though he’s now an original creation, he still retains a few subtle traces of Popeye, such as a large nose, a cleft chin, and a lumpy hat. Yet at the same time, he also appears to borrow from Mickey Mouse — most notably, his red pants with two large white buttons on the front.

Which raises an interesting question: When Miyamoto realized that he couldn’t use Popeye, why didn’t he just replace him with Mickey — a character who is a lot easier to render in just a few pixels? For that matter, why didn’t they go with Mickey from the start? Why Popeye?

Upon further investigation, I’ve arrived at two possible theories.

Theory #1: They Didn’t Have The Worldwide Rights

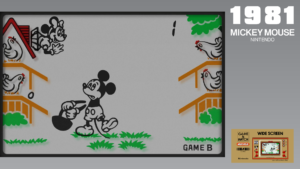

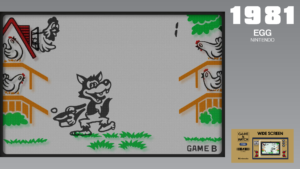

Game & Watch Mickey Mouse exists in two flavors: the normal version, and a generic version called Egg.

The reason? Nintendo only had the rights to sell Mickey Mouse products in Japan, so Egg was created for the international market while they worked on securing a worldwide license.

The process must’ve gone a lot more quickly than they were expecting, because both games were available in North America at Christmas time — though Egg was apparently produced in much smaller quantities, making it quite rare.

It makes me wonder if the reason Mickey had a Plan B was due to Nintendo’s previous experience with Game & Watch Popeye, which took half a year from concept to completion when most of the games took only two months, perhaps an example of how The licensing pipeline can be fraught with delays. The development of Donkey Kong would have been no exception.

What if the real reason they had to drop Popeye from the game is that Yokoi simply realized that if they were really in a hurry to crank out a Radar Scope replacement, a licensed game just wasn’t gonna be an option.

But none of this explains why the following year they still decided to do a Popeye game, when a Mickey Mouse game using that same graphical technique would’ve been absolutely huge in America. Why Popeye?

Theory #2: They Just Really Fucking Loved Popeye

On April 15th, 1983, Tokyo Disneyland opened in Japan. According to Nikkei Marketing Journal, this resulted in a sudden surge in popularity for Mickey Mouse, who had fallen behind more popular characters like Bambi and Pinocchio.

You can see this play out within the handful of Nintendo playing card catalogs that are viewable on the blog Before Mario. In the early ‘60s, there was a fair amount of Mickey, as well as Donald, Bambi, and Lady and the Tramp. But by 1975, there was no more Mickey, just Bambi and Lady and the Tramp. And then, in 1983 — the year of Tokyo Disneyland — a sudden explosion of Mickey.

Popeye was also featured in the 1960s and 1983 catalogs — and also missing in 1975 — but if a catalog from the late ‘70s ever surfaces, I strongly believe Popeye will be in there. Because in the second half of the ‘70s, Popeye suddenly experienced a surprise resurgence. During this period, he became — among other things — the spokesman for Ikari Sauce, the mascot for Japan Airlines ski vacations, the namesake of a fashion magazine for “City Boys,” and the subject of a hit disco song by a novelty group called Spinach Power.

Which raises the unlikely question: Could it be possible that, for a brief period of time between 1976 and 1982, Popeye was actually more popular in Japan (pause) than Mickey Mouse? Or, to ask an even more important question:

Why Popeye?

To be continued…

If you enjoyed this, please consider supporting the site on Patreon!

Notes

- I’ve listed several sources for this factoid in the next section down. Leland is the earliest:

“According to Nintendo, Mario’s Q rating — the measure marketers put on a celebrity’s recognizability — is higher than Mickey Mouse’s.”

Corr reports that “Mario outranks Mickey Mouse in popularity polls.” What polls aren’t specified, but the article later mentions that Nintendo Of America’s Howard Phillips has a Q Rating of his own, and “ranks about The Hulk, Pee-Wee Herman and just below Madonna Arnold Schwarzenegger.” Presumably the popularity poll referred to earlier would also be the Q Ratings.

Supporting this would be Haynes reporting roughly month later that “Mario’s ‘Q’ rating … ranks him ahead of Walt Disney’s endearing rodent.” Later that year, Rosenberg writes that “Nintendo’s publicists say his ‘Q rating’ (a measure of celebrity popularity) is higher than that of Mickey Mouse.”

By September 2020, Mario’s “Q Score” was just two points below Mickey Mouse’s, according to charts data revealed by Lindbergh. Currently unknown is how Mario compares to Mickey after the success of 2023’s The Super Mario Bros. Movie.

↩︎ - In Takefumi, Yokoi says, “I received an order from our company president asking if I could make a new game using the remaining [Radar Scope] circuit boards. … At the time I already had my hands full with designing the Game & Watch series, so I began the project with a pretty carefree attitude, having decided that out of the 3,000 unsold boards I had before me, if I managed to sell even just a few of them, like 1,000 or so, I’d be doing the company a favor…”

In comparison to Yokoi’s “carefree attitude,” Sheff characterizes Radar Scope‘s failure in America as an emergency. Maybe the stakes had not been communicated to Yokoi, at least initially.

Sheff also makes it sound like Yamauchi assigned the Radar Scope project directly to Miyamoto, but I believe Sheff was misunderstanding the sequence of event. In Iwata Asks, Miyamoto says, “Yokoi-san was good enough to bring these ideas to the President’s attention and in the end one of the ideas received official approval.”

↩︎ - According to trade magazines from the era, Wild Gunman and Shooting Trainer were initially distributed in America by Sega in 1976. Not long after, they were picked up by Bally, who also distributed Sky Hawk, Battle Shark, and New Shooting Trainer. Sheriff was distributed by Exidy under the name Bandido, and Sega/Gremlin distributed Space Firebird.

Space Fever, Color Space Fever, SF-HiSplitter, Space Launcher, and the cocktail versions of Sheriff and Space Firebird were distributed by a small company called Far East Video, whose founders became employees of Nintendo Of America in early 1981.

↩︎ - Sheff says: “When Yokoi later need help with games for Game & Watch, Yamuachi told him to use Miyamoto, since his other designers were busy with their own projects. ‘I asked him to do creation and I would supervise,’ Yokoi says.”

Sheff presents this as if it happened after Donkey Kong, but in Takefumi, Yokoi makes it clear it happened previous to that:

“In those days, Mr. Miyamoto’s job was package design. I called him over one day and told him ‘Let’s make a Popeye game for Game and Watch!,’ and so we began ironing out the concepts. But due to the aforementioned circumstances we instead decided to put it out on the remaining circuit boards as quickly as possible.”

Miyamoto seems to back this up in Shida and Matsui, where he says that Yokoi was interested in bringing in people from his department during production of Game & Watch before Donkey Kong.

When Sheff says: “Many of [Miyamoto’s] ideas for the game were rejected by Yokoi,” I believe this is referring to Miyamoto’s early pitches for Game & Watch designs rather than for the Radar Scope project.

Though it should be noted that Miyamoto contradicts Yokoi slightly in Iwata Asks, where he says “I asked if I could make a game using Popeye” rather than Yokoi asking him if he wanted to do a Popeye Game & Watch.

↩︎ - In Iwata Asks, Miyamoto describes this as “垂直リフト” which is translated as “vertical lifts” in the English version. In Shida and Matsui, Miyamoto instead says “シーソー” which commonly translates to “seesaw,” yet he’s clearly describing the vertical lifts and how they would be easier to move onto if one could jump.

When Miyamoto is asked about the “seesaw” a few years later in the UK publication Official Nintendo Magazine, he seems a little confused and describe a completely different concept that sounds like a literal seesaw or catapult.

↩︎ - Komanome’s sequence of events presents jumping as a concept that came up during the initial week of brainstorming before writing up the specifications, but whether it got its own button was not locked down immediately. Konanome says he recalls there being “contention” about whether jump should have its own button, and in Shida and Matsui, Miyamoto says the programming specifications indicated the button would be assigned to either “jump” or “hammer,” with a decision not made until halfway into development.

As far as who proposed jumping, it’s hard to say for sure because the Japanese language allows for a great deal of ambiguity unless someone very clearly specifies “this was my idea.” In Shmuplations’ translation of Komanome, he credits it to “we.” In Iwata Asks, Miyamoto credits it to “we.” Some translations of Yokoi have him saying “I,” but Florent Gorges admits the original text is still ambiguous. We may never know whose idea it was for sure.

↩︎ - Equally ambiguous is who’s idea it was for the game to contain four unique playfields. Komanome makes it sounds as though it was his team’s idea, explaining that the inspiration was Scramble. He also says “we” decided the four stage loop should play out in the four-panel kishōtenketsu style.

In a 2003 interview quoted in Chris Kohler’s Power Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave The World An Extra Life, Miyamoto says: “Thinking back, I would say that although it wasn’t done consciously, I ended up designing Donkey Kong like a traditional Japanese four-panel manga comic strip.” In contrast to Komanome’s version of events written in 1997, where it sounds like it was a very conscious decision, albeit one once again credited to “we.”

When telling the Donkey Kong story, Miyamoto sometimes includes an amusing anecdote that Ikegami complained that creating four unique playfields would be like creating four separate games, which would support it being his idea. But in Iwata Asks, he states that the complaint came from the technical supervisor, not the programmers, and I can certainly imagine that being a concern a supervisor would have even if the idea came from the team he was supervising.

↩︎

Sources

CHAPTER 1

- Leland, John. “When Kids ‘R’ Culture.” Newsday, July 15, 1990.

- Corr, Casey O. “Move To Level Two – Ho A Hurdle, Dodge A Fireball On The Way To Finding The Spirit Of America’s Favorite Toy.” The Seattle Times, December 16, 1990.

- Haynes, Rik. “Mario 4.” ACE, Issue 41, February 1991.

- Rosenberg, Scott. “Condemned To Be Mario.” IMAGE (San Francisco Examiner), September 1, 1991.

- Lindbergh, Ben. “More Than A Mustache: The Many Lives Of Mario, Video Games’ Most Malleable Mascot.” The Ringer, September 9, 2020.

- Makino, Takefumi and Yokoi, Gunpei. 軍平横井ゲーム館 [Gunpei Yokoi’s House Of Games], June 9, 1997. [Partial translation by End Of Deep Layer.]

- Sheff, David. Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered The World, 1993.

- Shida, Hideyuki and Matsui, Yuuki. ゲーム・マエストロ VOL. 1 [Game Maestro Volume 1: Producers And Directors], December 15, 2000.

- Gorges, Florent and Yamazaki, Isao. The History Of Nintendo, Vol. 1, November 20, 2012 [English edition].

- “Nintendo Sets New York Office.” Replay, Vol. VI, No. 4, January 1981.

- Pierson, David. “Play Meter Plays The Games.” Play Meter, Vol. 7, No. 1, January 15, 1981.

- Game Machine, No. 159, February 15, 1981.

- Replay, Vol. VI, No. 6, March 1981.

- “Mario Couldn’t Jump At First.” Iwata Asks: New Super Mario Bros. Wii, Nintendo, November 2009.

- “Arcade Game Technology: Special Edition – Donkey Kong: A Record Of Struggle.” Bit, Vol. 29. No. 4, April 1997. [Translation by Shmuplation.]

- “Masanobu Endo x Shigeru Miyamoto.” Family Computer Magazine, No. 7, February 1986. [Translation by Shmuplation.]

- “Shigeru Miyamoto Talk Asia Interview.” CNN, February 15, 2007.

- “Star System.” Tezuka Osaumu Official.

- “Miyamoto: The Interview.” EDGE, November 27, 2007.

- Kohler, Chris. “GameLife Reboot: Episode 018.” Wired, February 17, 2012. [Transcript from The Mushroom Kingdom.]

- Gorges, Florent and Yamazaki, Isao. The History Of Nintendo, Vol. 2, November 20, 2012 [English edition].

- “Test Models With Little Bulbs.” Iwata Asks: Game & Watch Ball, Nintendo, April 2010.

- “キャラクター最前線.” Nikkei Marketing Journal, February 17, 2000.

SPECIAL THANKS: Borp, Norman Caruso (Gaming Historian), Chris Chapman (Retrohistories), Alex Highsmith (Shmuplations), Dan Hower (Flyer Fever), Dustin Hubbard (Gaming Alexandria), Ethan Johnson (History Of How We Play), Nintendo Memories (Nintendo Memories), Nintendo Unity (Nintendo Unity), Old80s (Old80s), Alexander Smith (They Create Worlds), Benjamin Solovey, Tweakbod, Kris Vanderweit, Erik Voskuil (Before Mario), and The Secret Writers Society.

MUSIC: “Fast Talking,” “Cool Vibes,” “Backed Vibes Clean,” “Spy Glass,” “Deadly Roulette,” “Dances And Dames,” ” Walking Along” by Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/)

“Popeye The Sailorman” by Spinach Power.

Comments

Join the discussion in the Youtube comments!

December 11, 2023

[…] first of a planned five-part series), for which this translation was commissioned! The accompanying article she wrote is also very much worth […]