Riddle me this, Batman: What’s the opposite of a sleuth?

The opposite of a bat isn’t a cat, though at least it’s thematic. But why a detective’s opposite number be the person who deals in jokes instead of the one who deals in mysteries? I propose that Batman’s greatest rival isn’t the prankster whose calling card is a playing card, but the puzzler whose trademark is a question mark.

The Most Influential Comic Ever?

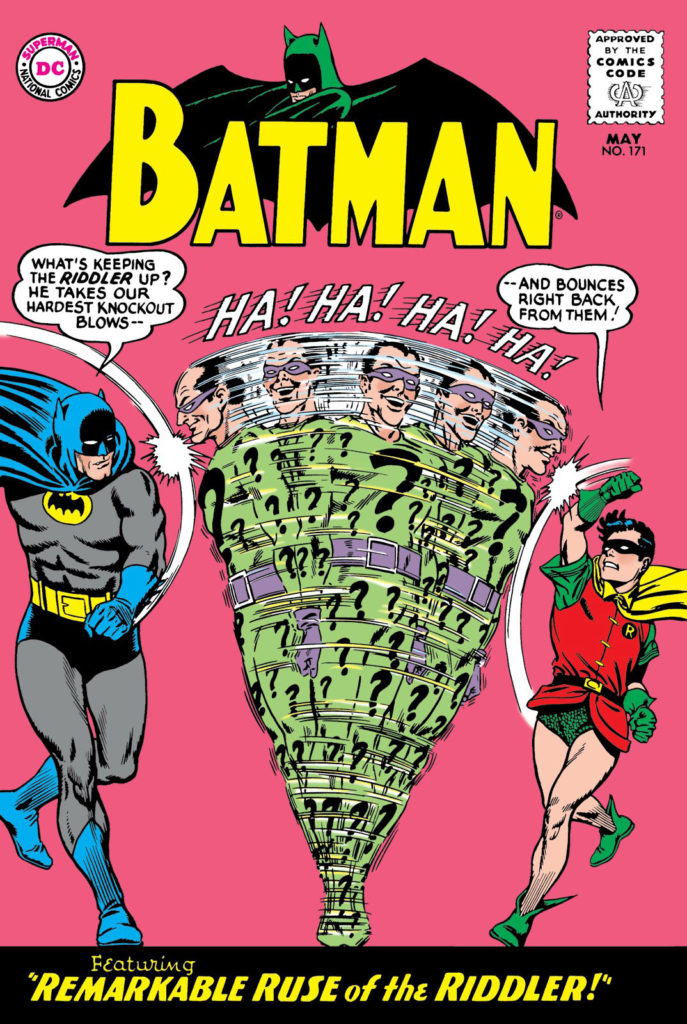

Batman #171 by Gardner Fox and Sheldon Moldoff might be the most influential comic in all of Batman’s history, if not in all of superhero history, because it was the basis of the most influential hour of superhero television.

The pilot episode of ABC’s Batman (1966), the hit TV series that — for better or worse — defined the public’s perception of superheroes for decades. I’d argue that even Tim Burton’s dark reimagining took as many cues from comics as from the show, with its stunt-casted villains and focus on “those wonderful toys.”

Like Burton, television producer William Dozier wasn’t much of a comics fan. But when he was assigned the project by ABC, Dozier went out and bought as many issues of Batman as he could find, new and old, paying as much as $4 a piece back issues! (Cover price was 12 cents at the time!)

That one of his pulls featured The Riddler is almost a miracle. The 1965 issue he based the pilot one was only The Riddler’s third appearance, a surprise revival of a character who’d previously only starred in two nearly forgotten stories from the ’40s. The character’s creators, Bill Finger and Dick Sprang — yes, those were their real names! — excelled at producing stories that were equal parts wacky and surreal.

But by the mid-’60s, there was a desire to make Batman more “serious.” However, in practice this didn’t result in stories that were necessarily smarter, just lacking in self-awareness.

For example, if you picked up Detective Comics #339 the same month as Batman #171, you’d find writer Gardner Fox and artist Carmine Infantino pitting the Dynamic Duo against a simian suicide bomber! Batman knocks out the guerilla gorilla and discovers that the bomb stops ticking when the ape is no longer in contact with the ground!

With all the strength he can muster, Batman holds “the living beast bomb” (as he’s referred to on the cover) over his head for as long as he can.

But eventually Batman runs out of energy and begins to falter. All hope seems lost as Batman drops the ape…only to discover that they’ve run the timer out! The day is saved!

The main difference between this and “sometimes you just can’t get rid of a bomb” is that the latter raises the stakes dramatically by placing innocent civilians everywhere, increasing both the tension and the absurdity. That was the trick Dozier figured out for how to make Batman appeal to both kids and adults while remaining (mostly) faithful to the comics: film it as a live-action cartoon played as serious as a heart attack.

And it worked! At least, as long as the kids and adults didn’t watch it together.

Why So Serious?

When the pilot episode aired, kids who thought it was an action show were confused by adults who thought it was a comedy. One newspaper critic reported his son told him to “stop laughing — this is serious!”

Admittedly, my relationship with the show has also been complicated. I first saw it during the late ’80s reruns launched in anticipation of the Tim Burton movie, and I absolutely thought it was a serious action series, albeit dated and not as “cool” as the ads for the new modern Batman.

As a teen, I discovered what the series had done to public perception of comic books, which led me to hate it. But now that superheroes are mainstream, I can appreciate the show for what it was: a comedy. Like the first time I rewatched Ghostbusters or Back To The Future as an adult and realized that those, too, were comedies. Comedies with awesome cars. What happened to all the sci-fi comedies with awesome cars?

Anyways, if you haven’t seen the pilot episode in a long time, you might be surprised to discover it’s actually “darkest” episode of the entire series. A large part of this is because it’s one of the episodes where the outdoor scenes are actually filmed at night, which also allowed for a rare appearance of the Bat-Signal! Filming during daylight was probably a budgetary decision.

But even more surprising, we hear Bruce Wayne actually mention his dead parents! In the ’60s show! They didn’t completely ignore it after all!

And in the second half of the episode, someone even dies! And they die in the Batcave! But I’ll get back to that. We need to talk about Frank Gorshin’s The Riddler.

The episode isn’t an exact retelling of issue #171 so much as “based on.” For example, the Molehill Gang are The Riddler’s henchmen in the show, but in the comic The Riddler actually helps Batman track them down!

The Riddler does this partly to convince Batman that he’s a good guy now, but also partly to demonstrate his clear superiority. Batman had been struggling for months to capture the Molehill Gang, but The Riddler is able to accomplish it very quickly. This clear superiority is another reason I consider him Batman’s greatest rival.

But the show is in a hurry to get to the first riddle, so it skips all this. And without thought balloons, The Riddler needs someone to exposit at, thus every Batman villain has henchmen. I suppose using the Molehill Gang as henchmen for this episode was easier than coming up with a gang from scratch, though they did invent a henchwoman named Molly for the gang, the only thing keeping the episode from being a complete sausage fest.

However, the show uses the first riddle verbatim, setting the tone for the entire series:

Probably the most significant difference between the comics and the show is Batman’s personality. The show made him much more “square,” i.e. very concerned with doing things responsibly and safely. He reminds Robin to buckle his seat belt, he orders orange juice from the bar since he’s on duty. Teenagers were apparently horrified at seeing their hero behave like a parent.

When Batman and Robin remove the bars from an upper-level window at the Peale Art Gallery, Robin is about to toss the bars to ground when Batman notes it could hit a pedestrian. He pulls out an adhesible bat-hook so they can hang it to the wall.

Turning their attention to the window, they spot The Riddler seemingly holding up an antiques dealer at gunpoint.

But it’s all a trick! After Batman chases and tackles The Riddler to the ground, The Riddler reveals the gun was simply a novelty lighter that he was using the light the dealer’s cigarette! Not only that, but The Riddler is actually the rightful owner of the antique they claim he was stealing!

In the comic The Riddler is merely playing with Batman’s head for the fun of it. But the show takes things in a much more serious, more realistic, and more adult direction:

The Riddler had photographers standing by so he could take the battle to the courtroom by suing Batman for false arrest! Except, if Batman can’t defend himself in court without taking off his mask and revealing his secret identity! The Riddler created the perfect trap!

And yet it was only a distraction from The Riddler’s true goal.

The Second Half

Each storyline in the first two seasons was spread across two 30-minute episodes with a cliffhanger in the middle. The pilot’s cliffhanger veers wildly from the comic issue, with Batman getting drugged by spiked orange juice and Robin getting kidnapped, not that things like this couldn’t happen in other issues.

A common trope in Batman comics was absurdly convincing masks, so henchwoman Molly is dressed up as Robin so she can infiltrate the Batcave.

If you’ve ever read Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, you might be asking yourself: is it possible that red-haired Molly was the inspiration for Carrie Kelley, whether consciously or subconsciously?

Molly succeeds in infiltrating the Batcave, but then the episode takes a surprisingly dark turn. Batman quickly discovers the ruse, and Molly tries to get away by climbing the Batcave’s atomic reactor, but slips and falls in! The only woman in the pilot with more than a single speaking line, and you can barely call it a “fridging” because it doesn’t even motivate anyone to do anything! The Riddler never even asks about her!

On the other hand, The Riddler later “dies” in an explosion in which is body is similarly never found. I wonder if they were leaving the door open for Molly to return as a radioactive supervillain?

But if you’re like me and you’ve seen Tim Burton’s Batman a million times, the images above might feel vaguely…familiar? It wasn’t until Tim Burton’s movie that The Joker’s origin involved him falling into a large vat of chemicals. Previously he accidentally swam through chemical drainage as part of a getaway, but it was never a fall into a vat.

Did this pilot inspire (consciously or subconsiously) both Carrie Kelley and the modern Joker? Did The Riddler’s complete disinterest in his henchwoman beyond a distraction inspire Harley Quinn?

Speaking of The Joker, let’s address the elephant in the room: actor Frank Gorshin’s portrayal on The Riddler is essentially The Joker without make-up. The Riddler from the comics wasn’t typically prone to maniacal laughter (outside of the cover to #171), but Gorshin’s performance alternates between frightening intensity and manic giggling.

The Joker comparison becomes even more obvious during the pilot’s final heist. Whereas the comic presented a pretty standard heist, with henchmen rounding up party guests and demanding their valuables while The Riddler cracks a safe in another room, the pilot went for something with a little more flair: laughing gas.

In a scenario likely borrowed from a Joker story Detective Comics #332, The Riddler filled the room with laughing gas and then performed a short stand-up act that causes the party guests to pass out from laughter. All while wearing a sharp suit and frilly tie that looks like it could’ve been borrowed right from the Joker’s closet.

Frank Gorshin’s The Riddler was always my favorite villain in the series, and I’m certain I wasn’t alone. His performance was so memorable, he instantly transformed the character from a C-list to an A-List villain. Unfortunately, the comics were hesitant to adopt this version of the character, likely due to the staff feel the same way as the readers about the show.

Or maybe it was due to the TV character being so similar to The Joker? No offense to Cesar Romero’s Joker, but Frank Gorshin really stole the show, and I imagine this version of the character would’ve overshadowed The Joker in the comics.

Gorshin’s Riddler was the superior Joker: he was funnier, scarier, and a better thematic fit. It makes more sense to confront a detective with puzzlers instead of punchlines, and that’s why The Riddler is Batman’s greatest rival.

But was Frank Gorshin actually the best Riddler? Tune in for Part Two of this essay — Same Bat Time, Same Bat Channel!

April 20, 2021

[…] Part 1 I made the case that Frank Gorshin’s Riddler was the best Joker. But was he the best Riddler? […]